One of the trickiest decisions a farmer has to make is keeping older cattle in their herd. While you may feel an affinity toward your older cows, keeping non-producing cattle for years is costly. The decision of whether to cull an older animal or keep it in your herd can be difficult and emotional.

It’s a decision I faced as I considered if I should keep three of my older bulls. They were the foundation of my herd for many years but did not successfully breed back cows last fall. As I’ve contemplated it, I talked with other cattle farmers to consider all aspects of this complicated issue.

What is the correct age to breed cattle? The correct age to breed cattle is 12-14 months old, although bulls can successfully breed at a younger age, and so should be separated from cows until you want to breed them. Heifers can become pregnant younger than 12 months, but an early pregnancy can cause health complications and limit the number of years she can successfully breed.

When a farmer culls too often, he or she may spend too much on animal replacements. Culling not often enough means that lower-producing cows are kept in the herd too long and eat up costly feed. A farmer needs to ask this question when facing the issue of culling an aged cow. “Is this cow producing more income for me than what I’m putting into her?” Or, “Is she costing me more compared to what she’s producing?”

It’s important to keep good records. Farmers who keep good production and health records find those record-keeping tools essential when determining how long to keep older cattle in their herd.

The reasons for keeping or culling a cow vary but ultimately, it depends on that cow’s usefulness and health (or projected health) and external factors like the current asking price for cull cows.

Culling cattle also factors into your whole-farm income. “Cull sales equate to 15 to 20 percent of [beef] cow herd income, so don’t overlook this opportunity to market high-value cull cows at the right time,” according to a Michigan State University Extension publication.

Here’s a rundown of reasons for knowing when to cull older cows in dairy, beef, and miniature cattle herds.

When Is A Cow Too Old To Breed?

On average, cows can regularly breed until they are eight to ten years old. Studies show that cows have high breed back performance until 8 years. Cows decline slightly in their breeding performance between 8 and 10 years of age. After 10 years of age, breeding performance declines sharply. At age 13+, reproduction capacity declines sharply.

As cows get older, they have a harder time breeding and carrying calves to maturity. A 10-year-old cow is approximately 50 years old. A 50 yr old woman wouldn’t naturally conceive, but a 10-year-old cow often breeds back, especially if she’s received high-quality care. Cows can regularly and successfully calf into their teens, which is the equivalent of a woman having a baby in her 70s.

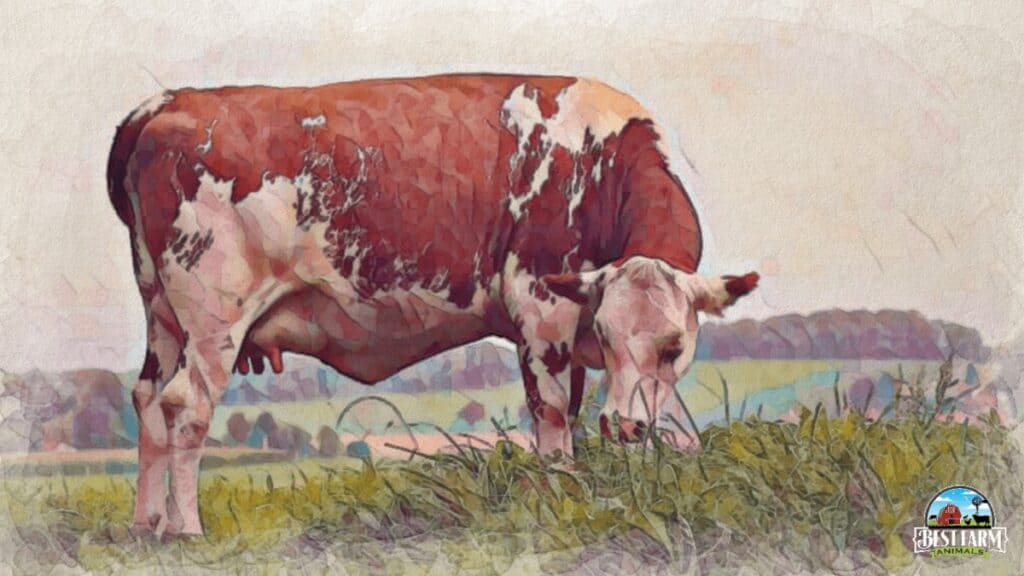

How Long Are Dairy Cattle Profitable?

Dairy cows are kept an average of 6 years, but annual records of dairy operations show that some dairy cows are kept until they are 8 or 9 years old. The biggest determining factor in keeping a cow is how much milk she produces, her success to breed quality offspring and the overall cost of keeping her physical health, including any diseases or detrimental living conditions.

- Disease—Diseased cattle rarely come back to total capacity. Time spent on disease prevention is less expensive than treating disease.

- Housing—Because of the concrete and getting in and out of the stalls, the bodies of dairy animals housed in free-stall barns tend to break down faster when compared to grazing animals.

- Physical problems—Prevent as many physical problems as possible to lessen involuntary culling. Cows 10 years and older who lose teeth may eat less and lose weight. Examine udders after calving. Examine the feet and legs of your cows. Cows with weaker feet and legs will get up to feed less often, be less able to stand for breeding should a bull be in the herd, and be less able to stand to nurse a calf.

How Long Do Cows Produce Milk?

Generally, cows produce milk between two and ten years old. The cow’s highest quantity of milk is usually between four and six years old. However, older cows can and frequently do give milk into their teens, though it will decrease in volume. Commercially, cows are not usually kept past ten years, so it is usually cows on smaller farms and homesteads that are kept and bred past ten years old.

Older cows may not always breed back and so may have missed years of not producing milk. They may have pregnancy or birthing issues. Almost always, an older cow that’s over ten years old, will produce roughly one-third to half of her maximum output when she was younger.

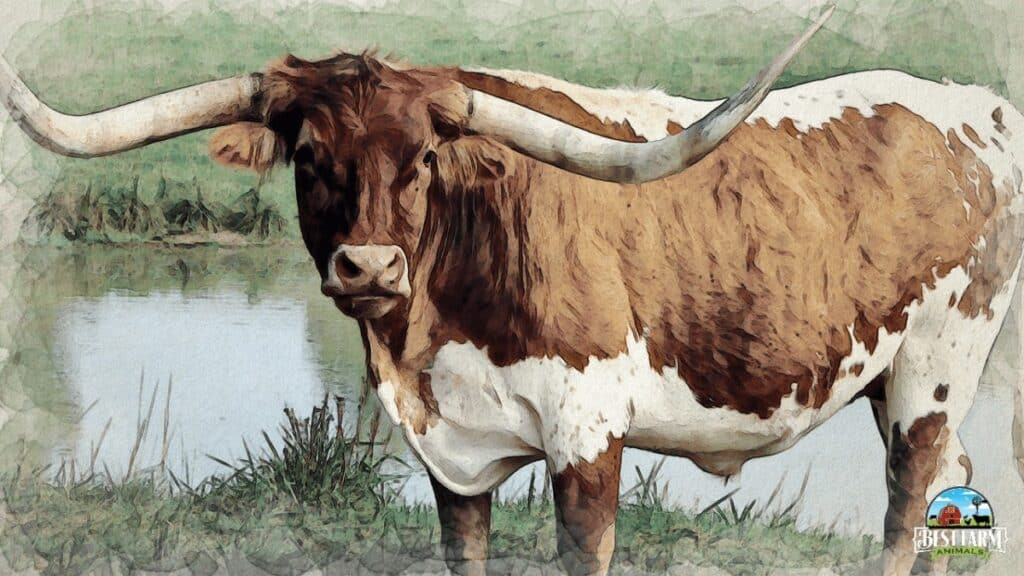

When Is A Bull Too Old To Breed

Bulls reach their peak reproductive health at around three years old. Most are bred until they are five years old. But, many bulls are capable of successfully reproducing into their teens. At age 12, a bull’s libido drops more drastically, and he may not be able to cover as many cows. That’s not an issue for many homesteaders, but the older bulls are culled commercially before their reproductive stamina drops.

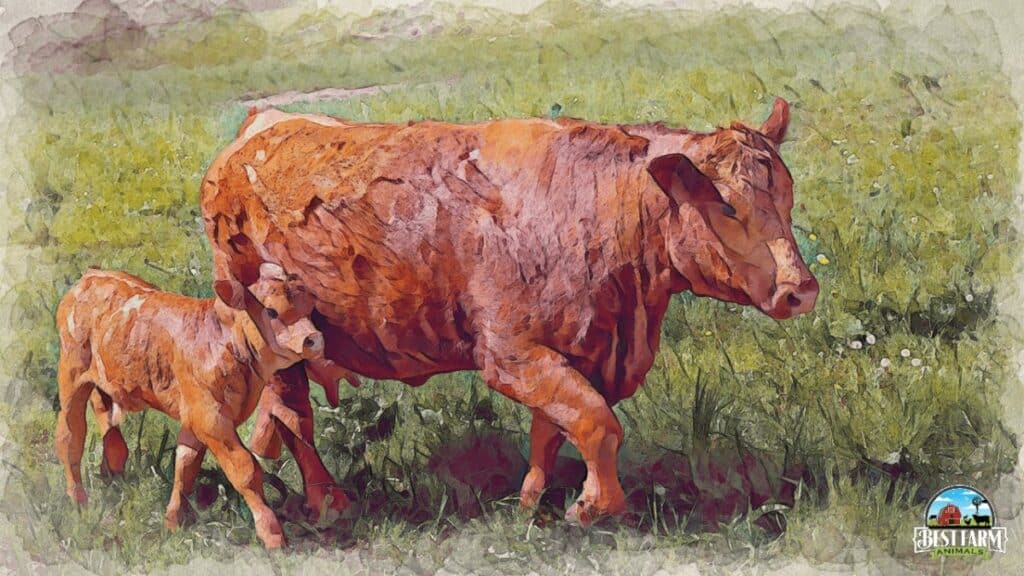

The Health of Beef Cattle Affects Early Culling

Deciding to cull an older beef cow depends on its fertility, health, calf replacement efficiency, and disposition.

- Fertility—Accuracy in pregnancy checks is essential. Check as soon after breeding as possible using ultrasound (on a 30- to 35-day old fetus) or rectal palpaters (on a fetus between 45 and 60 days). You do not want to sell a pregnant cow.

- Unsound physical features—Cull cows with less-than-optimal udders, teats, feet, and legs. Check the mouths of older cows.

- Nasty disposition—Each farmer has their own level of tolerance.

- Calf placement—Which cows constantly produce calves that rank at the bottom of your herd? Cull these, if possible.

How Old Keep Miniature Cattle

Miniature cattle breeds generally live for 20 to 25 years. They have a longer lifespan than other cows because miniature cows are often kept as pets or specialty herds. Because of the novelty of miniature cattle breeds, most owners don’t cull them as early as commercial dairy or beef operations. Miniature cattle can be raised for milk, beef, agricultural tourism, or as a novelty pet.

Cow Age to Human Years Chart

| Human Years | Cow Age | Human Years | Cow Age |

| 3 human months | 3.5 cow years | 10 human years | 50 cow years |

| 6 human months | 7 cow years | 11 human years | 54 cow years |

| 1 human year | 14 cow years | 12 human years | 58 cow years |

| 2 human years | 18 cow years | 13 human years | 62 cow years |

| 3 human years | 22 cow years | 14 human years | 66 cow years |

| 4 human years | 26 cow years | 15 human years | 70 cow years |

| 5 human years | 30 cow years | 16 human years | 74 cow years |

| 6 human years | 34 cow years | 17 human years | 78 cow years |

| 7 human years | 38 cow years | 18 human years | 82 cow years |

| 8 human years | 42 cow years | 19 human years | 86 cow years |

| 9 human years | 46 cow years | 20 human years | 90 cow years |

Although the above chart is generally accepted in translating human years to cow age, it isn’t completely accurate and is based on scientific estimates. In reality, cows can conceive and calf at an older age than humans can. While a 20-year-old cow can occasionally calf, a 90-year-old woman has never naturally conceived.

Age to Breed Cattle FAQs

How old can a cow get pregnant?

Most cows are bred between 12 and 14 months of age and reach about 55% of their mature weight when they first enter estrus. Conversely, if they are well-cared for, cows can continue to get pregnant as late as 15 and 16 years old.

The oldest cow to ever calf was Big Bertha who died at 49 years old and who calved 39 calves. I wasn’t able to find out how old Big Bertha was when she had her last calf, but it’s safe to say she calved into her late teens and likely was still calving into her early 20s.

How long should you keep a herd bull?

Bulls can be of service in a herd for an average of four to five years. Bulls can remain in service up to 10 to 12 years of age but don’t usually because of health problems. Bulls produce semen at about one year of age. Their ability to reproduce declines with age, which means that more bulls are needed for a herd of cows as the bull’s age.

How much does it cost to cull a cow?

Production animals become market animals when they no longer produce more income than they’re costing. Generally, the cost of culling a beef cow ranges from $200 to $400 per head. Dairy cow culling costs range from $500 to $1,000 per cow. Costs of culling can include animal replacement, lost production, transportation, and sale fees.

Conclusions

Choosing whether or not to breed an older cow will depend on how much that cows is a pet versus livestock. If the cow needs to maintain profitability, you’ll probably breed it back. But, if your goal is a longer life for a family pet- breeding back later in life can introduce health complications.

Recommended Cattle Supplies (And Dairy Supplies)

This list contains affiliate products. Affiliate products do not cost more but helps to support BestFarmAnimals and our goal to provide farm animal owners with accurate and helpful information.

This shelter is pretty easy to put together and it shelters a good number of cows. It’s sturdy and can withstand our high winds and heavy snows. And it’s cheaper than a barn and easier to build.

Colostrum is critical for calves. If you aren’t able to get some from your cows, this is a quality supplemental colostrum.

Probiotic for cattle with digestion issues in a oral tube. It works for other ruminants and is safe for goats, but is formulated especially for cattle.

A halter to lead Bessie around. This show halter also works for kids showing for 4H.

All Stock Feed is on Amazon, but you’ll pay less if you find it at your local feed store. It’s a great feed for cattle.

Electrical rope for your fencing. This keeps cattle in, but goats, alas- not so well.

Dairy Cow Recommended Supplies

Disposable towels or wet wipes are the first step in cleaning the udders.

Teat Dip and a dip cup are essential for keeping your milk clean. It lasts a while. Mine usually lasts a year to a year and a half.

I use a stainless steel bucket when I milk because it’s easy to clean and carry. These are my preferred milk filters and I use them for cow and goat milk.

This large jar funnel stays much more stable than regular funnels and can handle larger milk volumes.

I like this grain feeder while milking and use this size for the cows and goats being milked.

Balm ointment for sore udders. This cream is popular for people but formulated and created for cows’ udders.

Mastitis Test detects mastitis.